I-71's approach to the Lytle Tunnel now occupies this area.

Ft. Washington Way carries I-71,

U.S. 50, and provides access to downtown and the riverfront from I-75

and I-71. It was originally built between 1958 and 1961 and was

reconstructed

between 1998 and 2000. The reconstruction was complete -- today

no ramp, retaining wall, or sign post remains from the original

expressway, and with the implosion

of Riverfront Stadium in 2002, its environs have changed considerably

as well. The reconstructed Ft. Washington Way is the

newest

expressway in the Cincinnati area and is a major component of the

city's

ambitious

riverfront development scheme. Click Here

for the Ft. Washington Way reconstruction article.

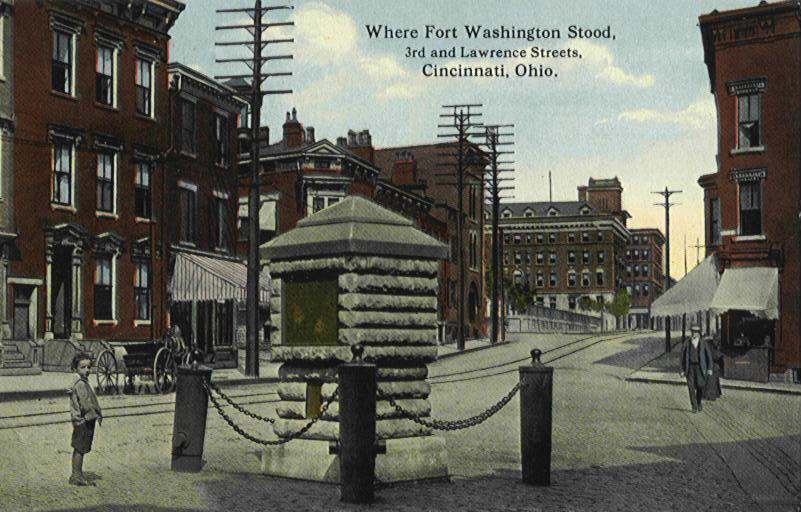

Ft. Washington Way was dubbed the "3rd St.

Distributor"

in the 1947 Expressways Master Plan, but was renamed during

construction

when the remains of Ft. Washington (1789) were unearthed near the

Broadway

overpass. The major elements of the expressway were, from east

to

west: the 3rd

St. Viaduct, the I-71 Lytle

Tunnel interchange, the "mainline trench",

and the I-75/6th

St. Expressway interchange. Construction

began soon after the Interstate Highway Act was passed in 1956, and the

3rd St. Viaduct opened in 1959, followed by the mainline trench in

1960.

The

Brent

Spence Bridge and I-75 interchange opened in 1963, and the 6th

St. Expressway (U.S. 50) opened in 1964. The Lytle Tunnel and

the I-71 interchange opened in 1970. The limited I-471

connections from the 3rd St. Viaduct opened in 1977.

I-71's approach to the Lytle Tunnel now occupies this area.

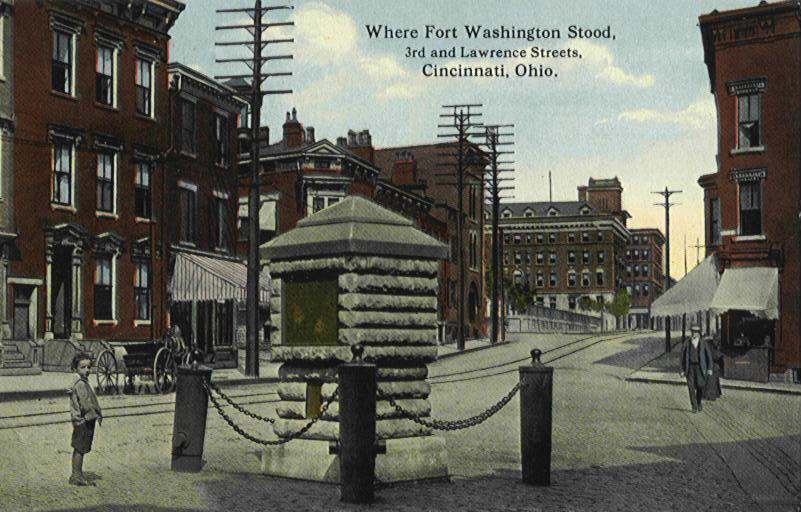

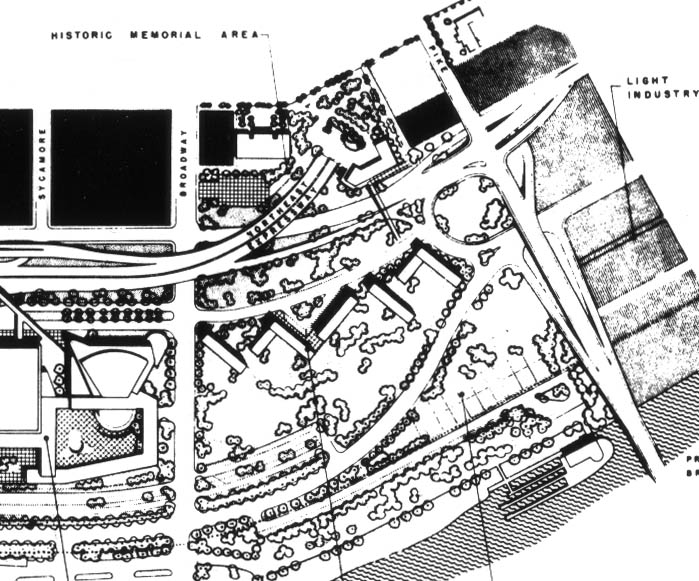

In the 1939 conceptual drawing below the

Distributor is seen as the ultimate destination of both a widened Linn

St. and Columbia Parkway:

In this drawing we also see an extension of the

C&O Bridge's vehicular approach to the foot of Plum St., skirting

the large warehouse that was demolished in 1998 to make way for the

Cincinnati Bengals' practice fields. To

the east, a shorter viaduct connects the Central Bridge to the base of

Broadway. A new street atop a levee parallels the Distributor in

a similar fashion to the Levee Way that opened in 1960 and was removed

in 2000. The

Distributor continues at ground level to its eastern connection with

Columbia Parkway without a viaduct, descending into the flood

plain. In the distance, we see the

widened Linn St. connected to a similarly widened 8th St. Viaduct

approach.

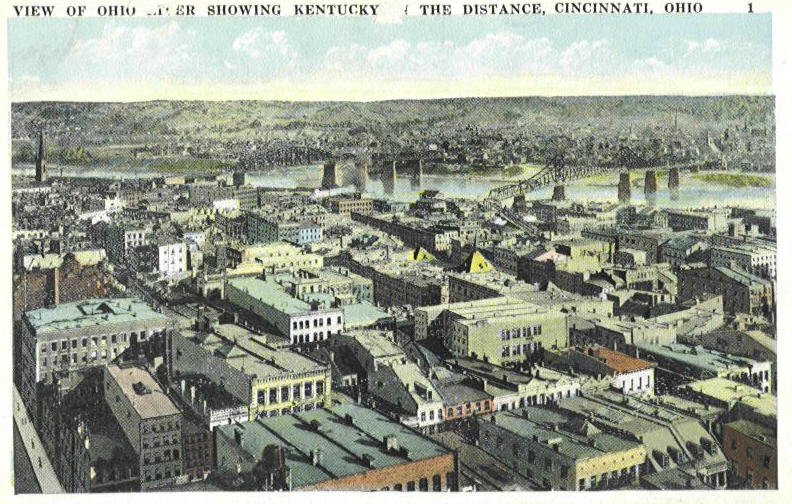

Linn St. was in fact widened along with Liberty St., Ezzard Charles

Drive

(formerly Lincoln Ave.), and 8th St., contemporary with I-75's

construction. The

entire West End (the thousands of mid-1800's row houses pictured to the

left of the business district) was demolished and replaced with public

housing blocks, light industry, and I-75 after WWII.

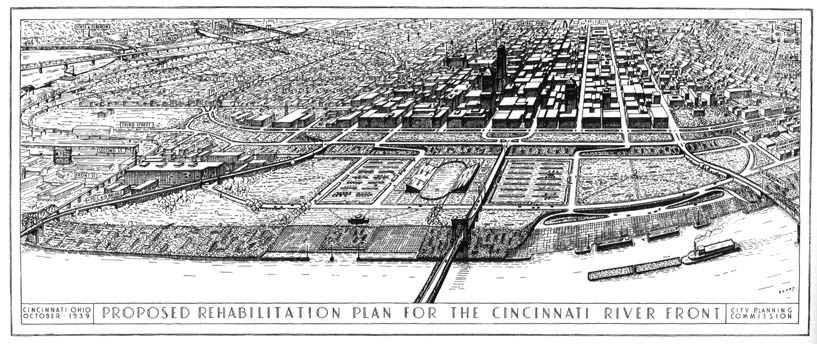

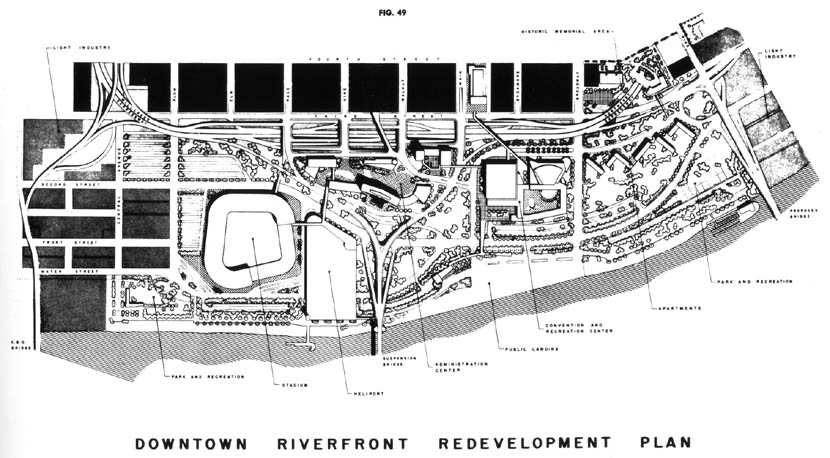

An expressway and riverfront

redevelopment graphic published in 1948.

Click Here

for a larger version of this graphic.

The 1948 plan, shown above, is closer to what was

actually built in many respects as compared to the 1939 proposal.

Here the Distributor is seen as the connector for the newly proposed

Millcreek Expressway, as opposed to a widened Linn St., and the

proposed Northeast expressway as compared to simply Columbia

Parkway. Interestingly, a Lytle Park Tunnel is shown more or less

precisely where it was built twenty years later, but the orientation of

its northern portal is not shown and confused by a proposed Pike St.

bridge to replace the then 60 year-old Central Bridge (The Central

Bridge survived 102 years until its demolition in 1992). As

built, the Lytle Tunnel's northern approach severed Pike St., and it is

today among downtown's most obscure streets. If a bridge had been

built there, it is reasonable to assume that the park's tunnel would

have been extended so that Pike could reach as far north as 5th

St. As in the 1939 drawing, no new Covington bridge is foreseen,

and the C&O is awkwardly incorporated via a narrow elevated

viaduct. It goes without saying that the the proposed stadium,

heliport, civic buildings, and apartments were drawn with little

serious thought.

A close-up of the proposed Lytle Park Tunnel and Pike St.

Bridge.

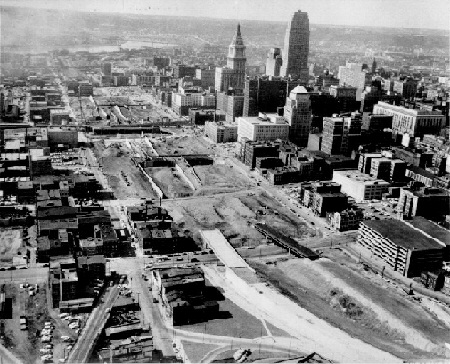

Fort Washington Way under construction 1957 or 1958.

The old Central Bridge's approach can be seen at bottom left, forming

a 5-way intersection with Broadway and the original 2nd St.

As built, the Distributor differed significantly from either of

the two above proposals. Having learned from the

instant failures of Boston's Central Artery (recently demolished in

2004 and replaced by the $12 Billion Central Artery Tunnel) and the

handful of recently opened New York City expressways,

Cincinnati's 3rd St. Distributor included breakdown lanes and merge

lanes considered adequate for the time. But the trench's six

through lanes kinked slightly out of parallel with the street grid, and

like Boston's Central Artery, far too many entrance and exit ramps made

for stressful conditions. In fact, after the opening of the

Lytle Tunnel in 1970, Fort Washington Way's 23 entrance and exit ramps

(including six left-side ramps) in the span of one mile were the most

of

any expressway in the country. Cars

frequently backed up from the short exit ramps onto the through

lanes,

and those on entrance ramps often stopped at the bottom and then waited

for a minute or more for an adequate gap.

Site of Fort Washington Way prior to major construction.

The

5th St. Viaduct is at bottom right.

Another early 1990's view [Larry

Stulz photo]

Two more overpasses were built concurrent with the opening of Riverfront Stadium in 1970. These two bridges connected the stadium plaza with north/south alleyways that bisected their respective city blocks. The overpasses touched down halfway between 3rd & 4th St. where east/west alleys further divided their blocks into quadrants. The bridges were built at the stadium's plaza height and permitted taxis and pedestrians to reach the stadium directly from downtown. The eastern bridge was modified in 1980 with the construction of the Atrium 1 building, which blocked the alleyway but connected directly with the new building's lobby. A partial roof was added to this bridge in the mid-1980's, and large panels illustrating moments in Cincinnati Reds history were added later in the decade. This bridge was shared by pedestrians and taxi cabs, and rowdy fans regularly slapped the hoods and windows of passing taxis.

The western bridge was modified in 1990 to allow for construction of the 30 floor 312 Walnut building, which was soon after renamed The Scripps Center. Unlike the Atrium 1 complex, the block's alleyway was not severed and could still be used by pedestrians who knew of its existence, although most took stairs to the intersection of 3rd & Walnut. With this modification taxi service stopped and a full roof was added soon after. This roof turned the bridge into an echo chamber, adding natural reverb to the sounds of street musicians and heft to post-game chants.

Ft. Washington Way and the pedestrian ramps during summer 2000

reconstruction.

[Jake Mecklenborg August 2000]

The east pedestrian/taxi bridge -- the postgame surge of humanity often

prevented taxis from

using the bridge. The two bridges stood connecting nowhere to

nowhere following Riverfront

Stadium's implosion in December 2002, and were not fully dismantled

until the summer of 2003.

[Jake Mecklenborg Summer 1999]

This notch marks the spot where the east bridge crossed.

It is among the only remaining vestiges of the original Ft. Washington

Way.

[Jake Mecklenborg November 2004]

In the 1990's trees and unkempt foliage overgrew

most

of the grassy areas along the levee and north side of the

expressway.

A small park of less than an acre, similar to the extant Firefighter

memorial

between Central Ave. and I-75, existed at the base of Elm St. By

the time reconstruction commenced in 1998, it had become completely

overgrown

and forgotten.

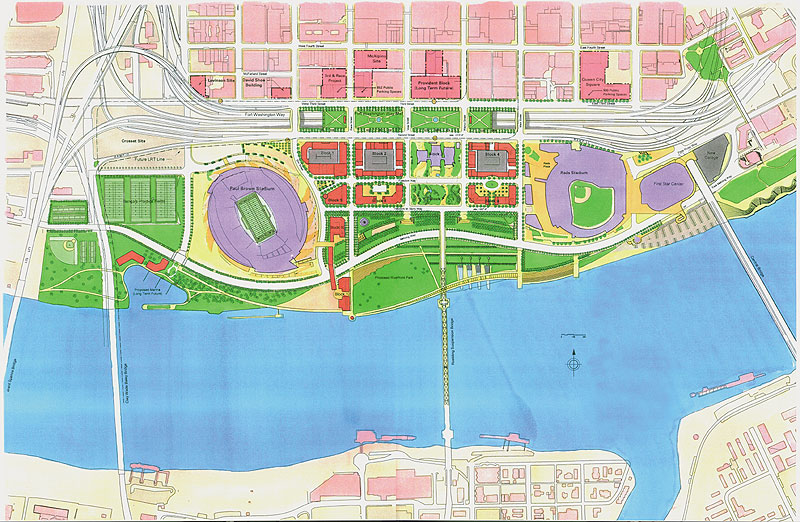

Ft. Washington Way and Riverfront Redevelopment

Model of Cincinnati created by the Cincinnati Department of

Economic

Development.

Although the color coding is complex, generally the

lighter colored buildings have either been constructed

or proposed

since 1964, including some projects under construction in late

1982.

Photograph (1982) by Michael Isaacs.

The above photograph and caption were taken from Daniel

Hurley's Cincinnati: The Queen City,

published in 1982. Along

with the two from earlier in the century and the more recent ones

below, it is obvious that redevelopment of Cincinnati's central

riverfront has had no shortage of proposals or difficulty in

sustainability. The eastern riverfront was redeveloped in the

1970's and 1980's -- The Serpentine Wall, Yeatman's Cove park, and

Bicentennial Commons have proven to be great assets. Wheras

the strip-like eastern riverfront was developed mostly with public

funds and serves mostly as park land, the central riverfront is an

immense area which has required much more money and time to develop.

Another graphic from 1999.

What can be learned by viewing old proposals is that what is

actually built and isn't is entirely unpredictable. They

are also frequently drawn by people who don't live in Cincinnati and

don't have much familiarity with the place (the above 1999 graphic

shows the old Central Bridge, which was dismantled in 1992). In

the recent graphics, Ft. Washington Way was indeed rebuilt as shown,

but its covering lid has not. Paul Brown Stadium at left and

Great American Ballpark at right have been built, as has the National

Underground Railroad Freedom Center. The park at the base of the

Suspension Bridge and surrounding apartment and commercial development

have not, and will not until later in the decade. The right-most

proposed skyscraper is under construction, but will only reach about

fifteen floors.